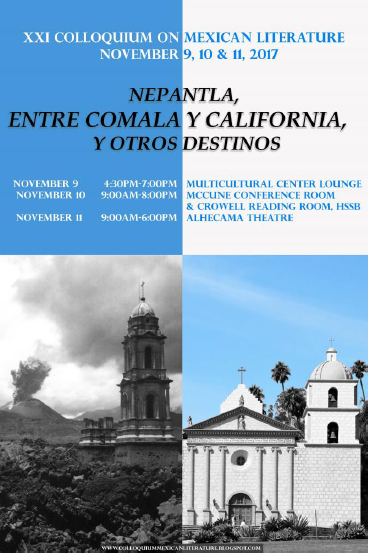

XXI Colloquium on Mexican Literature. 9-11 noviembre 2017. University of California, Santa Barbara. Participan: Sara Poot-Herrera y Patricia Saldarriaga

Consultar Programa

This year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Juan Rulfo (1917-2017), author of El Llano en llamas (The Burning Plains and Other Stories) and Pedro Páramo. We also celebrate the 50 years of Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude). Gabriel García Márquez once said his novel was indebted to Pedro Páramo. Could that be? Let’s take a look:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” (One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967).

However, not only textual quotations link these two books—of all books!—their very fabric weaves from one to the other. Fifty years later, we appreciate the traces of Pedro Páramo in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Both invite the reader to leave momentarily. To go beyond two worlds, two books, and in between: Nepantla? Commemorating the centenary of Juan Rulfo between two worlds, two countries, is a gesture of gratitude toward a brief but infinite piece of work, compact and fragmented, spoken and written—a pendulum between past and future (perhaps similar to our present?)—about violence and impunity, the crucial crossing of borders, of ghost towns, of economic migrations, of looting along the way, of the daring and the embittered. His brief literary work was premonitory: the violence, the injustice, diaspora, and poverty that suffocates Mexico had already been referenced in Rulfo’s poetic words. “Mexico isn’t finished yet,” he once said, and his words are like Articles of faith. His work, our Mexican Bible, is the book of prayers that we read in and outside of Mexico.

In keeping with our tradition, and sustained support at UCSB, now a Hispanic Serving Institution, given these urgent and uncertain times, and with a daily commitment to affirming a cultural image of Mexico outside of Mexico, this twenty-first conference on Mexican literature centers on how Mexican cultural production travels, crosses toward the North, arrives at these latitudes. We think above all about the connection between Juan Rulfo’s narrative—scenarios and characters—and the Latino communities on the map of the United States where, as in Mexico and other places, there are ghost towns, men and women who recall the flight of a kite during their childhood and remember this experience, in their own language, be it Mexican, English, or Spanglish.

Some time ago I wrote, “A question for Carlos Monsiváis: ‘Those in Los Angeles, do they not return to Comala even for their blankets?” Do those from Luvina prowl the coasts of California? Do American universities hold the first generations, branches of the trees—pruned, fallen, reborn —where genealogy is also kept the same but modified by language, history, geography, crossroads? Caw, caw, caw.

Hence our colloquium focuses on the historical and geographical relationship between Comala (imaginary geography of Pedro Páramo) and California, along with other destinations (and I refer to California, the state where we are in this country, Agripina, but also to other states of which you know more). The people of Comala may have left for California, but they never really left. Their mind and spirit remained in Comala. Thus, forming a suspended existence, a place that is neither Comala, nor California, but Nepantla. Agripina, but also other states, of which you know even more.

Geographically Nepantla is a Mexican town (Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was born there). It is a word in Náhuatl that, while itself a single word (prodigious of language), situates two places. Beyond that, it is also a concept and an identity. We are Nepantla, meaning “in the middle,” “between,” “among,” “in between.” Nepantla, just one word refers to two worlds. In the 16th century, a member of the original peoples of the center of Mexico, said to Fray Diego Durán, “Do not be afraid, Father, because we are still Nepantla.”

Our conference (dear all, “where we are all Nepantla”) deepens the discussion of what has been hitherto sketched out. We know this: every year has its own anniversaries, commemorations, celebrations, festivities. 2017 is the centenary of Juan Rulfo and Leonora Carrington, and also of Pedro Infante, who died in 1957, in Mérida, Yucatán, México! Twenty years later, in 1977, Carlos Pellicer, who was born in 1897, dies. And also “El rey criollo” (“The Creole King”) by Parménides García Saldaña: Elvis Presley.

2017 is a year of Mexican literary commemoration. With the signature of Alfonso Reyes, a filigree booklet—Visión de Anáhuac—is in its 100th year of publication. Among other titles re-read and read (and thus celebrated): Al filo del agua / The Edge of the Storm (1947); Balún Canán andLibertad bajo palabra/ Freedom under Parole (1957);Morirás lejos/ You will Die Away; Zona sagrada / Sacred Zone and Cambio de piel/ Skin Change (1967); Amor perdido/ Love Lost (1977); Muchacho en llamas/ Boy in Flames (1987); Guerra en el paraíso/ War in Paradise(1991/1997); Revolucionarios mexicanos/ Mexican Revolutionaries (1997); A los pies de un Buda sonriente/ At the Feet of s Smiling Buddha (2007); Última escala en ninguna parte/ Last Scale Nowhere (2017).

Let their now-absent authors again read to their readers what they wrote for them, books that transit between themselves, in the paths and their pages, and through other authors who will also be discussed and celebrated on November 9 th , 10th, and 11th.

In spite of the rumors, as Juan Rulfo would have said [and our mouths fill to repeat it], “Mexico is not finished.” To stand up for Mexico (even while we’re abroad), is our obligation, our ethical responsibility, and our nobility.

NEPANTLA, BETWEEN COMALA AND CALIFORNIA, AND OTHER CROSSROADS will reunite us in our traditional November here in Santa Barbara. Welcome!

Sara Poot-Herrera

Dejar un comentario

¿Quieres unirte a la conversación?Siéntete libre de contribuir!